In the silent chambers of ancient tombs, where time stands still and whispers of forgotten civilizations linger, archaeologists often uncover more than just skeletal remains. Among the dust and decay, there lies a glittering testament to human creativity and cultural expression: jewelry. These artifacts, meticulously crafted and placed alongside the deceased, serve as portals through which we can glimpse the aesthetic sensibilities and technical prowess of bygone eras. The study of funerary jewelry is not merely an exercise in cataloging precious objects; it is a profound journey into the hearts and minds of ancient peoples, revealing what they cherished, how they perceived beauty, and the remarkable skills they employed to immortalize their values in metal, stone, and glass.

When a piece of ancient jewelry is unearthed, it arrives in the modern world as a puzzle wrapped in layers of soil and time. The initial discovery is just the beginning. Archaeologists and conservators engage in a delicate dance of preservation and analysis, employing tools ranging from soft brushes and microscopes to advanced technologies like X-ray fluorescence and scanning electron microscopy. Each piece is cleaned with painstaking care to avoid damaging its fragile structure, and every speck of surrounding material is sifted for clues. The context of the burial is paramount; the position of the jewelry on the body, the materials used, and the presence of other grave goods all contribute to a richer understanding of its significance. For instance, a necklace found clasped around the neck of a high-status individual in a Mycenaean shaft grave speaks volumes about social hierarchy, while a simple bead buried with a child in an ancient Mesopotamian site might reveal tender aspects of familial love and beliefs in the afterlife.

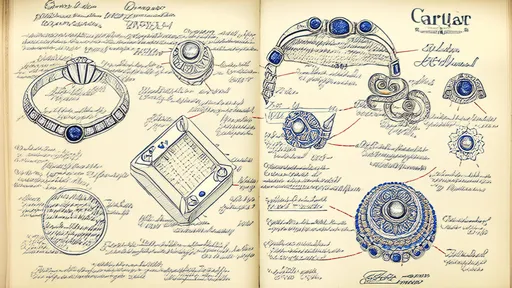

Beyond their symbolic meanings, these adornments are masterclasses in ancient technology. The metalsmiths of antiquity worked without modern machinery, yet they produced items of astonishing complexity and refinement. Consider the granulation technique perfected by the Etruscans, where tiny spheres of gold were fused onto a surface to create intricate patterns without any visible solder. This method, which still baffles modern jewelers in its execution, points to a highly sophisticated understanding of metallurgy and temperature control. Similarly, the lapidary arts of the Indus Valley Civilization, where carnelian beads were etched with white patterns using an alkali paste, demonstrate a chemical ingenuity that was far ahead of its time. By reverse-engineering these processes, researchers can map the evolution of technical skills across cultures and centuries, tracing the transfer of knowledge along trade routes from the workshops of ancient Egypt to the forges of classical Rome.

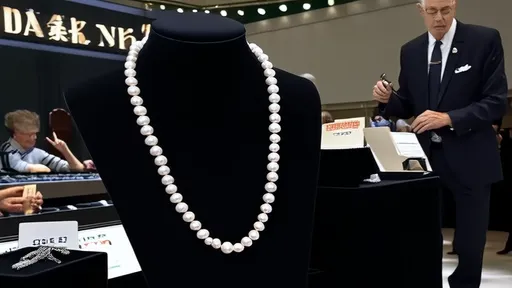

The choice of materials in funerary jewelry also opens a window into ancient trade networks and economic systems. A single necklace might tell a story of global connections long before the term globalization was coined. Amber from the Baltic coast found in Egyptian tombs, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan gracing Sumerian royalty, and pearls from the Indian Ocean adorning Roman empresses—all these materials hint at vast exchange networks that spanned continents. The value ascribed to these substances was often tied to their rarity, color, and perceived mystical properties. For example, the deep blue of lapis lazuli was associated with the heavens in many cultures, making it a favorite for amulets and divine representations. By analyzing the provenance of these materials through isotopic tracing and other scientific methods, archaeologists can reconstruct ancient trade routes with surprising accuracy, showing how our ancestors were interconnected in ways we are only beginning to appreciate.

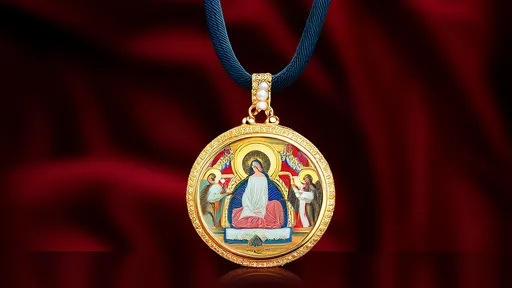

Perhaps the most intimate insights gleaned from funerary jewelry relate to personal and social identity. In death, as in life, jewelry communicated status, affiliation, and belief. A Celtic torc, worn tightly around the neck, was not merely an ornament but a symbol of warrior status and tribal loyalty. The elaborate gold wreaths of Hellenistic kings, mimicking leaves and berries, were designed to associate the wearer with divine authority and eternal glory. Even in more egalitarian burial contexts, the presence of jewelry—a copper ring, a shell bracelet—suggests a universal human desire to be remembered and to carry something meaningful into the beyond. The wear patterns on these items can be particularly revealing; a ring worn smooth on the inside speaks of a long life of use, while a pristine, overly ornate piece might have been created specifically for burial, indicating ritual practices and beliefs about the afterlife.

However, interpreting these ancient treasures is not without its challenges. The ravages of time often leave jewelry corroded, fragmented, or stripped of its original context by looting and early archaeological practices that prioritized object collection over contextual recording. Moreover, our modern perspectives can color interpretations; we might see a gold diadem as a symbol of wealth and power, while its original wearer might have valued it primarily for its protective spiritual properties. Ethical considerations also loom large, especially when dealing with human remains and culturally sensitive items. Collaborations with descendant communities and interdisciplinary approaches that blend archaeology with anthropology, art history, and materials science are essential for developing more nuanced and respectful understandings.

In the end, the jewelry buried with the dead does more than adorn skeletons; it revives voices. Each bead, each clasp, each finely wrought motif is a word in a silent language of beauty, belief, and skill. From the glittering gold of the pharaohs to the humble clay beads of commoners, these objects remind us that the human impulse to create and to beautify is timeless. As we continue to unearth and study these treasures, we do not just reconstruct ancient techniques and tastes; we weave a more connected and compassionate tapestry of human history, one where the past is not dead but vividly, brilliantly alive.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025